Today marks the 85th birthday of Martin Luther King Jr.

85. It seems so old. Except my grandfather is older than the age MLK would have turned today. I’m an 80’s baby – a millenial. The 50’s and 60’s seem like generations upon generations ago.

Today, King Jr.’s “I Have Dream Speech” will likely be replayed on media clips nation wide. The similar stories will be told and another MLK day will move on. For most cities, unfortunately it’s been relegated to a “moving holiday.” Atlanta has branded it more as a “day on” versus a “day off.” I dig it.

On the days surrounding MLK Day, I find it more insightful to understand the context of speeches or timing behind decisions. After some thought, it occurred to me there was never a “big moment” in Atlanta civil rights wise. Unlike the initial sit-ins in Greensboro, bus boycotts in Montgomery, the images broadcasted nationally of german shepherds and water hoses in Birmingham, or national guards guiding desegregation in Little Rock — Atlanta, Georgia seemed to miss almost every national headline when it came to contentious race relations. After all, we were the “city too busy to hate.” Atlanta, more specifically Auburn Avenue, was the mecca for people of color in the mid 20th century.

How did Atlanta remain above the fray?

We didn’t have a seamless integration of races in our city. However, city leaders prioritized pragmatism above anything else and it took every ounce of persuasion, restraint (from all parties), and honest-to-God trust building to keep Atlanta a progressive, Southern city in a time where bigotry and hate pervaded our region.

Reverend King Jr.’s finest moment in his home town spurred everything but a headline.

In early March of 1961, students of the AUC were in a heated negotiation with Atlanta’s old guard of powerful black leadership. Daddy King (Martin’s father), John Wesley Dobbs, Reverend Borders, and other established leaders were debating with students how to handle the terms of desegregating lunch counters in Atlanta. Downtown merchants were willing to desegregate lunch counters and other facilities but not before the scheduled desegregation of the schools later that fall. Black Atlanta was putting faith in white Atlanta’s word via a written contract — the first one ever.

Young, anxious students didn’t want to wait another 6 months for desegregation, especially on a stipulation as fragile as the school system integrating. Tension between the old guard of black Atlanta and students climaxed when Daddy King exclaimed: “BOY, I’M TIRED OF YOU” as he waived his finger to the then AUC student leader, Lonnie King (no relation) on the fourteenth floor of the Commerce Club.

Days later the pot of emotions began to overflow.

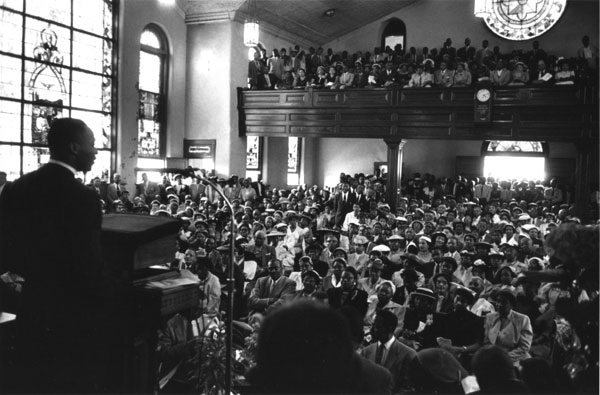

On March, 10 1961, 2 years before his famous march on Washington, Martin Luther King Jr. sat in a filled Warren Memorial United Methodist Church with over a thousand gatherers in attendance on an evening breaming with contempt. Few whites were in the church, including a soon-to-be-elected Mayor, Ivan Allen Jr.

Historians wrote “the ingredients of a riot” were there.

Daddy King took the stage and reminded them that he had been working for civil rights in Atlanta for three decades. Immediately a woman in the audience stood and shouted, “And that’s what’s wrong!”

After three hours of heated discussion, where many of Atlanta’s old guard were disrespected including the president of the local branch of the NAACP, Reverend Sam Williams, the time had come for Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to take the stage.

Witnesses claim “his eyes were a little glassy” due to the crowd’s rejection of his father.

Then in a voice familiar to every one in the church, Reverend King, Jr. began, “I’m surprised with you.” His twenty-minute oration in which he said, “We must see in this struggle that Aunt Jane, who knows not the difference between ‘you duz’ and ‘you don’t,’ is just as significant as the Ph.D. in English.” Misunderstandings are not solved “trying to live in monologue; you solve it in the realm of dialogue.”

He continued about the “cancer of disunity” and the “palpitation of purpose.”

“If this contract is broken it will be a disgrace,” Reverend King exclaimed as his voice rocketed through the public address system into the streets of black Atlanta. “If anyone breaks this contract let it be the white man.”

At the end of his twenty minutes, Reverend King Jr. achieved a “unity of spirit” among the crowd’s disparate groups. Atlanta’s first written agreement amongst white and blacks was in serious danger of unraveling before tonight.

Ivan Allen Jr. had heard blacks refer to Martin Luther King Jr. as “Little Jesus.” Never again would he wonder why.

*some excerpts were taken from Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn